The HRP undoubtedly requires an ability to understand your own limits. You must be able to look at a map and accurately estimate how many hours or days the next supply point will be for you. You must be able to look at a particular crossing or foothold and know with certainty if it’s unsafe. You must be able to grit your teeth. You will be tested, you will feel the apathy of a harsh environment as you attempt to cross it. It will be unpleasantly cold and unbearably hot and your gear/clothes will be be pushed to their limits.

Physical fitness is essential. I spent the year prior exercising and I dropped my body weight from 240 lbs down to 190. I got my mile run time down to almost 7 minutes. Yet with previous experience, strong legs and will, I still spent that first week on the trail in desperation wondering how I would carry on.

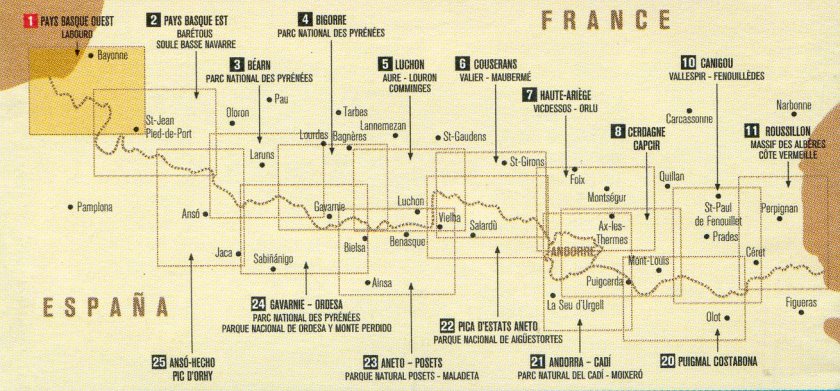

Knowledge of reading terrain – you really need to get topographic maps. I also highly recommend the accompanying guide book by Cicerone as a primary navigational resource. You’ll have to adjust to the author’s style of route description and understand how the physical landscape translates to text. The route is a string of mountain passes, sheep paths and village roads with mixed signage – some places are well marked and others are not marked at all. You need to be able to look across a valley and understand where you’re climbing out. Can you bunker down should those ominous clouds form a lightening storm overhead, or are you going to be caught on an exposed section? How will you find the road when the scree slope you are descending is blanketed in fog? How safe is the upcoming portion of trail if I were to continue in the dark, and does my headlamp have enough battery?

Now, the reason you’re here – Necessary Technical ability. The most severe terrain equates to snow-covered passes and large boulder fields. There are plenty of wide dirt (and paved) roads, plenty of nice meandering foot paths through lush valleys. But know that you will be required to scramble up exposed rocky slopes and over teetering ridges, you will be slipping along steep gravel slopes and jumping between large boulders. There are a few river crossings without bridges. There will be portions with snow year-round, where you want to have an ice ax and crampons. Some of these you can find alternate routes to, others are unavoidable and require an appropriate level of alpine skill & equipment to safely traverse.

On the other end of the scale, your street smarts will be tested as you inevitably take many kilometers of mountain roads, both dirt and paved. You will have to hug the road shoulder and railing along high-trafficked motorways. This can perhaps the most dangerous part of the whole route.

Once in the heart of the range, about every other day my heart would be racing as I psyched myself up and gaged my ability to make it across a sketchy portion of the route, knowing a mistake would require search and rescue efforts. Certainly each day in the middle three weeks presented an opportunity to slip up and seriously hurt myself.

Water is perhaps the most unforgiving in this list. While my British companions carried roughly 0.75L – 1L water and did fine, I typically had 3 times the amount. This is very taxing in terms of weight but became a necessity for me to stay hydrated day-to-day. I also can’t stress enough how this ties into the above point about knowing the terrain; Can you accurately estimate how far water points are, given the anticipated conditions and your ability? If the source were dry, how far is the next one? If you were to become critically injured, would you have enough water to last for the longest time frame before help arrives?